Overview

As directed by Executive Order 12866 and other statutory and administrative requirements, this final regulatory impact analysis (Final RIA) assesses the economic impact of the final rules revising the regulations of the Department of Justice that implement Titles II and III of the ADA (Final Rules), including estimates of the impact of these rules on small entities. The Final RIA presents a comprehensive benefit-cost analysis of the final rules, assessing the likely incremental impact of nearly 120 “requirements” (i.e., individual revised regulatory provisions, or closely-related groups of revised provisions, that are expected to have an incremental cost impact relative to the Department’s current 1991 Standards) across more than 65 different types of public (Title II) and private (Title III) facilities.

Methodology and Framework. The cost-benefit analysis estimates costs and benefits during the time the Final Rules will be in effect as new facilities are built (“new construction”), existing facilities undergo otherwise planned alterations (“alterations”), and existing facilities undergo barrier removal to comply with supplemental requirements not eligible for safe harbor (“barrier removal”). The analysis assumes that buildings have an average lifespan of 40 years and that these rules will likely be superseded by new rules in 15 years.

The analytical framework largely mirrors that of the initial regulatory impact analysis (Initial RIA) that accompanied the Department’s notices of proposed rulemaking published in the Federal Register in June 2008. As with the Initial RIA, monetized costs in the Final RIA reflect initial capital outlays for design and construction, as well as applicable recurring costs (such as, for example, ongoing operation and maintenance costs for a required pool lift, replacement costs for a standby power for platform lifts, or the value of a change in productive space due to revised clearance requirements for single-user toilet rooms). The analysis also accounts for costs to users and cost savings to facilities when a less stringent requirement leads to decreased accessibility. Sections 3.1 and 4.1 of the Final RIA detail the methodology and assumptions underlying the estimation of monetized costs. On the benefits side of the economic calculus, the Final RIA incorporates only use-related benefits to persons with disabilities from changes in accessibility attributable to the final rules. These benefits are measured and given a dollar value based upon the requirements’ impact on the amount of time needed to access or use a facility, on improvements in the quality of facility access, or enhancements to the quality of facility use. Detailed discussions of the methodology and assumptions underlying the estimation of monetized benefits are provided in Sections 3.2 and 4.2 of the Final RIA. Other benefits and costs that cannot be quantified due to methodological and data constraints – which for benefits, in the context of these final rules, are undoubtedly significant – are discussed in qualitative terms and explored through a series of threshold analyses in Sections 6.5 and 6.6 of the Final RIA. The Final RIA also uses risk analysis to more realistically address some of the inherent uncertainties underlying the benefit-cost analyses. See Final RIA §§ 3.3, 4.3 (discussing “Risk Analysis” approach) & App. 6 (RAP Primer). Lastly, the Final RIA incorporates changes as compared to the Initial RIA to reflect public comments, updated information/data, and modifications to regulatory provisions in the Final Rules. These updates and revisions are summarized in Chapter 5 of the Final RIA.

Overall Results. The overall results of the Final RIA show that the Department’s Final Rules are expected to generate total benefits to society that are greater than their measurable costs under all studied scenarios. Chapter 6 of the Final RIA provides a complete summary and discussion of the results of this regulatory analysis. Most significantly, under the primary baseline scenario used throughout the Final RIA (i.e., 1991 Standards baseline, safe harbor applies, and 50% readily achievable barrier removal for elements not covered by safe harbor), the Final Rules are expected to have a total net present value (NPV) of $9.3 billion (7% discount rate) and $40.4 billion (3% discount rate). See Final RIA, Tables ES-1& 6 (reproduced below); Figure 8.

Total Net Present Value in Primary Scenario at Expected Value (billions $)

(Under Safe Harbor, 50% Readily Achievable Barrier Removal, 1991 Standards for baseline)

| Discount Rate | Expected NPV | Total Expected PV(Benefits) | Total Expected PV(Costs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3% | $40.4 | $66.2 | $25.8 |

| 7% | $9.3 | $22.0 | $12.8 |

Results Summary – Costs. The Final RIA shows that construction costs for new facilities are generally expected to be lower than the capital costs for other types of construction (i.e. under alterations or barrier removal). Indeed, nearly one-half of the requirements are expected to have no capital costs or to incur a cost savings as compared to the current 1991 Standards for newly constructed facilities, as architects can “design around” many requirement in the planning stages with minimal cost impacts and some requirements are less stringent and, therefore, less costly. See Final RIA, App. 3-H (Unit Costs). Only three facility groups are projected to have new construction costs that total more than $26 million over the lifecycle of the final rules: private nursery schools/day care centers; private exercise facilities; and, private aquatic centers. See Final RIA – Supplemental Results (“Supp. Results”), pp. 14-149.

For existing facilities generally, costs of compliance with the Final Rules will be incurred primarily through alterations. The need to make additional changes to comply with these rules during alterations occurs only when an entity voluntarily undertakes an alteration project, and, even then, generally applies only to the particular elements undergoing alteration. Overall, alterations costs vary greatly by facility group, with some facilities experiencing minimal alterations costs (or even cost savings) overall under the final rules (e.g., stadiums, convention centers, auditoriums, airport terminals, public parking facilities, public theaters/concert halls, jails, prisons, bowling alleys, fishing piers, and public amusement parks), and other facilities projected to incur relatively higher costs when undertaking alterations (e.g., hotels, motels, restaurants, single-level stores, indoor service establishments, offices of health care providers, private aquatic centers, and office buildings). See Final RIA – Supp. Results, pp. 14 - 149. The variability in alterations costs are largely driven by the mix of affected elements in each respective facility group.

Barrier removal, by contrast, is a continuing obligation that applies to all public areas of existing Title III-covered private facilities. The Department’s Final Rules, however, provide an element-by-element “safe harbor” provision that is designed to mitigate the impact of these rules on existing private facilities. This safe harbor provisions exempts such facilities from barrier removal obligations so long as unaltered elements comply with the current 1991 Standards. As a result, many private facilities are expected to incur minimal costs (or no costs) for barrier removal. Indeed, when taking the safe harbor into account, over one-half of the 38 facility groups comprised of Title III-covered (private) facilities are projected to incur no barrier removal costs. See Final RIA – Supp. Results, pp. 14 - 149. To be sure, some existing private facilities will incur barrier removal costs under the final rules due to the presence of elements subject to supplemental requirements for which safe harbor is inapplicable. Title III-covered facility groups with expected barrier removal costs that are higher relative to their respective new construction costs include: private amusement parks; private colleges and universities; exercise facilities; aquatic centers; and, miniature golf courses.

Results Summary – Benefits. Turning to the benefits side of the equation, as noted above, the Final RIA puts a dollar value on the use-related benefits to persons with disabilities (estimated using the value of time) arising from changes in accessibility attributable to the final rules. Requirements with the largest monetized benefits (i.e., requirements expected to generate over $700 million in monetized benefits respectively during the lifecycle of the final rules) include: passenger loading zones; water closet clearance in single-user toilet rooms with out-swinging doors; side reach; bathrooms in accessible guest rooms at lodging facilities (vanities and water closet clearances); accessible exercise machines and equipment; accessible route to exercise machines and equipment; primary accessible means of entry to pools (new construction/alteration); accessible means of entry to wading pools; and, accessible means of entry to spas. See Final RIA, Table 7.

The Final RIA also acknowledges that the final rules will undoubtedly confer substantial and important benefits that cannot be readily quantified or monetized. In this sense, the regulatory assessment must be considered conservative since it almost certainly understates the overall value of the final rules to society. Few would doubt, for example, that the psychological and social impacts of the ability of persons with disabilities to fully participate in public and commercial activities without fear of discrimination, embarrassment, segregation, or unequal access have significant value. Society generally will also experience benefits from the final rules that are difficult to monetize, including: reduced administrative costs (from harmonization of the final rules with model codes); increased worker productivity (due to greater workplace accessibility); improved convenience for persons without disabilities (such as larger bathroom stalls used by parents with small children); and, heightened option and existence values. In addition to unquantifiable benefits, there may be negative consequences and costs as well, such as costs if an entity defers or foregoes alterations, potential loss of productive space during additional required modifications to an existing facility, or possible reduction in facility value and losses to some individuals without disabilities due to the new accessibility requirements. The Final RIA discusses these and other costs and benefits not estimated in the main analysis in qualitative, rather than quantitative, terms. See RIA §§ 6.5, 6.6.

Executive Summary

With the adoption of the revised regulations implementing Titles II and III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (Final Rules), the Department of Justice (Department) has commissioned this final Regulatory Impact Analysis (Final RIA or final regulatory analysis). The Final Rules incorporate the 2004 ADA Accessibility Guidelines (2004 ADAAG) published by the Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board (Access Board) on July 23, 2004. The Access Board conducted an assessment of the potential cost of its revised guidelines but did not assess benefits. This analysis develops and executes a method for estimating both benefits and costs of the Final Rules.

This Final RIA is intended to accompany the Final Rules. The initial step in this process was the publication in the Federal Register of a proposed framework for the regulatory analysis, presented as Appendix A to the Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM), which was published by the Department on September 30, 2004.[1]

Notices of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) for the proposed Title II and Title III regulations were subsequently published on June 17, 2008. A complete copy of the initial regulatory analysis (Initial RIA) conducted by HDR/HLB Decision Economics Inc. was posted on the Department’s ADA website (www.ada.gov).[2] In addition, appendices presenting detailed descriptions of the proposed revised ADA standards, the Department’s responses to ANRPM comments concerning the proposed methodology for the initial benefit-cost analysis, and a summary of the Initial RIA were also published in the Federal Register.[3] The public was given 60 days to submit comments. The Department reviewed and considered the public comments received in response to both the proposed regulations and the Initial RIA. As a result, regulatory revisions have been incorporated into the Final Rules. A discussion of the Final Rules and the Department’s responses to NPRM comments relating to the substance of the proposed regulations can be found in the Preambles to the Final Rules. The Final RIA, as well, incorporates changes to estimates, assumptions, and certain aspects of the cost and benefit models in response to public comments on the Initial RIA. The Final RIA estimates the total costs and benefits of the Final Rules, as revised in response to public comments and as a result of further research or updated data sources.

Dimensions of the Regulatory Analysis

Incremental Effects

The economic costs and benefits of the Final Rules are estimated for existing and new facilities. Costs and benefits are measured on an incremental basis. That is, the economic impact of the Final Rules is represented by the change in benefits as compared to previously enacted access regulations. The primary baseline of the analysis is the 1991 Standards. However, some states and local jurisdictions have adopted more current model codes with different accessibility standards (such as International Building Code (IBC) 2000, IBC 2003, and IBC 2006) and these represent alternative baselines.

Type of Construction

The Final Rules impose costs for different types of construction: New Construction, Alterations and Barrier Removal. New construction and alterations apply to new construction of buildings and major renovations at existing sites, respectively. Such projects are thought to involve design opportunities for incorporating accessibility features called for in the Final Rules. Alterations projects take place on existing buildings but are expected to be undertaken on a regular schedule. By contrast, barrier removal projects are assumed to be smaller in scale and undertaken specifically to comply with the Final Rules.

Facilities Subject to Final Rules

The Final Rules adopt standards for new construction and alteration of facilities covered by Title II (which applies to state and local governments) and Title III (which applies to private entities operating commercial facilities or “public accommodations” as defined by the ADA). For purposes of the final regulatory analysis, public (Title II) and private (Title III) facilities are categorized separately into 68 facility groups or types. Types of facilities include single purpose facilities, such as hotels and classes of facilities, such as retail stores (e.g. clothing, laundromats) or service establishments (e.g., banks, dry cleaners). In some cases, facility groupings are defined based on the size of the facility (e.g., auditoriums and convention centers). Other groupings are based on economic characteristics, especially the responsiveness of average customers to changes in prices for goods and services at facilities. For example, grocery stores and restaurants are in different groups because consumers would have less price responsiveness in shopping at a grocery store than going to a restaurant, since most people can cook at home. Finally, it must be noted that some requirements, such as exercise equipment, may be elements in larger facilities, such as hotels. Benefits from using such elements are assumed to be conditional on facility use.

The Department is adopting a Safe Harbor (SH) provision for existing private (Title III) facilities already compliant with the 1991 Standards. Under Safe Harbor, elements at these existing facilities will not need to undergo barrier removal for revised requirements so long as these elements currently comply with the 1991 Standards. Barrier Removal is not relevant for public (Title II) facilities. Instead, separate program accessibility or “program access” requirements ensure that programs or services offered by a public entity at existing facilities are, when viewed in their entirety, accessible to and usable by persons with disabilities. Program accessibility requirements, however, do not require that every existing facility be made accessible so long as the overall program is itself accessible. Nonetheless, the Final Rules provide that elements in existing public (Title II) facilities that are already compliant with the 1991 Standards or UFAS, are not subject to retrofitting due solely to incremental changes reflected in these Rules. This analysis thus assumes that Title II entities will not need to make changes to existing facilities except in the limited context of supplemental requirements applicable to public play areas, swimming pools, saunas and golf courses.

Description of Requirements

Over one hundred substantive changes to the 1991 Standards and existing ADA regulations are included in this analysis. These changes include two kinds of requirements – supplemental (or “new”) requirements and revised requirements. Supplemental requirements have no counterpart in the 1991 Standards and the Department is adopting them into the ADA Standards for the first time. They are comprised of provisions from the Board’s supplemental guidelines relating to State and local government facilities (1998), play areas (2000), and recreation facilities (2002).[4] These requirements apply to elements and spaces that are typically found only in certain facility types, such as courthouses, jails, prisons and a variety of recreational facilities.[5] In some cases, elements subject to new requirements (e.g. swimming pools) are located in facilities that have been subject to the 1991 Standards.

Revised requirements relate to elements or spaces that are currently either subject to a specific scoping or technical requirement in, or are specifically exempted from, the 1991 Standards. They generally apply to elements and spaces that are found in a wide range of commonly used facility types, such as restaurants, retail stores, schools, hospitals, and office buildings. Some revised requirements apply to common building elements (such as windows) and commonly used facility types (such as residential dwelling units) that have no counterpart in the 1991 Standards, but have long been subject to specific accessibility requirements or guidelines from other sources.[6] All of the revised requirements were adopted by the Board in 2004, and all were described in the Board’s final regulatory assessment for the 2004 ADAAG.

Revised requirements fall into two categories, both of which are defined relative to the 1991 Standards: “more stringent” and “less stringent” requirements. Generally speaking, more stringent requirements increase accessibility compared to current requirements, potentially conferring a greater benefit to the general public and imposing a greater cost upon facilities. Less stringent requirements relax standards relative to the current requirement, potentially causing a loss of benefits from access but reduced costs for facilities.

Analytical Scenarios

To assess the implications of the Safe Harbor provision for existing facilities that are compliant with the 1991 Standards, this analysis provides two sets of results, one with and one without safe harbor. Under the safe harbor, the Department deems compliance with the scoping and technical requirements in the 1991 Standards to constitute compliance with the ADA for purposes of meeting barrier removal obligations. Only elements in a covered facility that are in compliance with the 1991 Standards are eligible for the safe harbor. Thus, under the safe harbor scenario, barrier removal is not required for revised requirements and changes to facilities proceed on the alterations schedule.

To determine the proportion of existing elements that will likely undergo barrier removal or alterations, the analysis utilized the following factors:

- The number of buildings constructed before and after 1993. The proportion of building constructed before 1993 is represented by (c). The buildings constructed after 1993 would be “new” compared to the 1991 Standards and they are assumed to be compliant with the 1991 Standards.

- Elements constructed before 1993 are then sub-divided into whether they have or have not been altered between 1992 and the projected effective date of the Final Rules. The proportion of facilities altered after 1992 is represented by the proportion (b).

- Elements are either subject to more stringent or less stringent requirements. Elements subject to less stringent requirement are not required to undergo barrier removal. Elements subject to more stringent requirement are classified by whether barrier removal is or is not readily achievable. If barrier removal is not readily achievable, the element will become compliant under its alterations schedule. The proportion of elements assumed to be readily achievable is (a).

These conditions imply different cost and construction processes depending on whether the requirement is less or more stringent and whether Safe Harbor is adopted. Data is used to determine (b) and (c); (a) is evaluated under different analytical scenarios.

The 2004 ADAAG was developed with the intent of harmonizing, to the greatest extent possible, the revised requirements with the International Building Code (IBC). IBC baselines are applied where they are more stringent than the 1991 Standards and equivalent to the Final Rules. Separate analyses of these baselines are conducted as scenarios.

Methodology Overview

Approach to Benefits

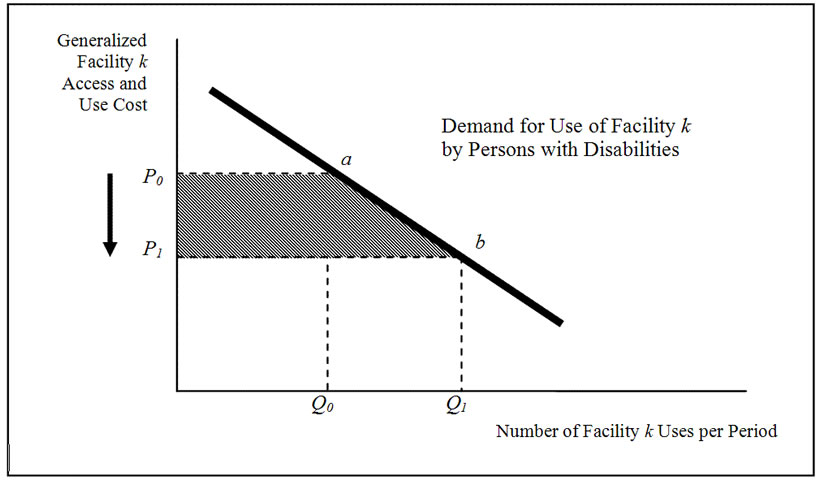

Benefit-cost analysis principles are applied to help inform whether the incremental benefits of the Final Rules are justified in economic terms. Benefits from improved accessibility can be categorized either as “use” benefits - incurred because of the use of a facility or requirement - or as non-use benefits. The latter category can include the value of knowing that greater accessibility exists should it be needed in the future and the value of believing that civil society is improved, among others. Use benefits can also be further differentiated among those which accrue from use by persons with a disability and those that accrue from use by a person without a disability (such as the parent with a stroller making use of a curb cut). In the underlying methodological framework of this analysis, use benefits that consumers derive from changes in facility accessibility are generated from changes in the quantity and quality of time spent entering that facility, as well as consuming goods and services there. Benefits are primarily represented by the creation of economic value from these changes in quantity and quality. The “generalized use and access cost” of a facility visit is the basis for determining use value. The actual price paid for goods and services represents only part of this “generalized cost.” Users also incur costs as a manifestation of the time spent traveling to a facility and the time spent within a facility accessing the spaces or features which constitute the primary purpose of the visit. For example, people go to movie theatres to watch a film. Likewise, one goes to a restaurant to eat or to a hotel (as a guest) to sleep. In such cases, the access time is the time that a visitor spends within a facility to move from say, the parking lot, to her or his seat, table, or bed. In contrast, use time refers to the time spent watching the movie, eating, or sleeping.

This distinction is important because changes in accessibility due to the Final Rules have a direct impact on access time and the quality of the experience for users while visiting a facility. Users derive value from a visit from three distinct sources:

- Changes in access time;

- Enhanced quality of facility access; and

- Enhanced quality of facility use.

Each of these components of value can be monetized with an appropriate “value of time,” namely, an expression of a user’s willingness to pay for changes at the facility. With regard to the first component, minutes saved in accessing a fishing pier, for example, can be monetized by a value of time that depends on the reason for using a facility. That is, facilities that principally involve leisure activities have a lower value than ones involving work, including housework.

The components (b) and (c) identify benefits that are derived from a change in the experience of accessing and using a facility. Enhancing the quality of facility access means changing the experience of moving through doorways, getting a drink of water, or getting into a pool, for example.

Requirements that cause an incremental change in access time -- addressed by component (b) -- enhance value during the entire duration of access time change. Use time -- addressed by component (c) -- is enriched by requirements that fundamentally change the experience of using the facility. For example, requirements that enable users to fish off a pier, use an assisted listening device to better enjoy a lecture or exhibit, or place their wheelchair in a space that does not overlap a circulation path experience increased value throughout the time that they are participating in those activities.

Yet, while this methodological framework assesses and monetizes significant benefits to users with disabilities due to changes in the quantity and quality of facility access and use that can be attributed to the Final Rules, the model nonetheless does not (and cannot) capture the full range of benefits which may accrue from these Rules. User benefits that are neither quantified nor monetized in the final regulatory analysis include: a reduction in stigmatic harm or avoidance in humiliation experienced by a person who uses a wheelchair who can, for the first time, use the single-user toilet room at a restaurant independently due to enhanced clearances; or the sense of integration felt by a high school student with a mobility impairment who can directly access the stage in the school auditorium for school events along with his or her classmates instead of having to use a “back alley” route to the school stage; or the improved safety afforded persons with mobility or visual impairments by having handrails on all stairs that are part of a means of egress. Likewise, this final regulatory analysis does not attempt to quantify use-related benefits that persons without disabilities may experience as a result of improved accessibility from the Final Rules (such as a parent with a stroller making use of a curb cut). Lastly, this analysis neither quantifies nor monetizes non-use related benefits arising from the Final Rules, including any cross-sector benefits, option/insurance values, existence values, or third-party employment benefits.

Approach to Costs

The incremental cost of compliance for facilities includes initial and recurring costs. Initial costs

refer to the capital costs incurred for design and construction at the facility to achieve

compliance. Recurring costs include, as applicable, operations and maintenance (O&M) and loss

HDR | HLB DECISION ECONOMICS INC. xv

of productive space. In addition, to maintain compliance with some requirements, facilities will

need to incur costs to regularly replace equipment. More stringent requirements involve

increased capital costs whereas less stringent requirements offer facilities capital cost savings.

Recurring costs follow the same cost structure as capital costs.

While the model quantifies and monetizes the costs to facilities in many areas, facilities or users may incur costs in areas that are not quantified or monetized in the model. Such areas include, but may not be limited to, costs from deferring or foregoing alterations, loss of productive space while modifying an existing facility for compliance with those few requirements for which safe harbor does not apply, and reduction in value and losses to individuals without disabilities due to the new accessibility requirements. Some other costs such as potential administrative costs associated with new requirements are estimated in a sensitivity analysis. The absence of a quantitative assessment of such costs is not meant to minimize their importance to individual users or entities that may place a higher value on them. Rather, this analysis does not separately quantify such costs based on the assumption that, given their comparatively low overall cost to society, incorporation of risk analysis (e.g., probability distributions for estimated cost variables) already adequately captures their relative impact on total net value of the Final Rules.

Lifecycle Analysis

Annual costs and benefits are computed over a long-run planning horizon and summarized by a

lifecycle cost analysis. The Department expects that a new rule will be adopted in 10-15 years

given the current congressional mandate. Accordingly, it is assumed that 15 years after this rule

becomes effective, approximately 2026, construction costs at new buildings and associated

accessibility benefits will not be applied to this rule. It is also assumed that existing buildings

undergo barrier removal in equal proportions each year as construction costs become potentially

readily achievable.

Annual costs and benefits are assumed to extend for 40 years for each building that complies with the Final Rules. The rationale of 40 years is based on the premise that almost all buildings will have been substantially altered by then. The lifecycle analysis also assumes that (a) it takes several years before benefits at a facility reach their full potential; (b) some elements require replacement over and above maintenance costs; and (c) remaining value in the compliant element is captured as a salvage value. Real discount rates of 3.0% and 7.0% are applied to all future costs and benefits as a representation of how the public and private sectors view investments.

Incorporating Uncertainty

Uncertainty in the estimation of costs and benefits is addressed through risk analysis. Risk analysis principally involves quantifying the uncertainties in factors for estimating costs and benefits. Quantification involves defining probability distributions of possible values for each factor. Data used to quantify uncertainty comes in part from research and discussions with experts. The distributions of cost and benefit factors are inputs to the model, which is then solved using simulation. The simulation process varies all factors simultaneously so that interrelationships between variables are more realistically handled and the impacts of factors on final results are considered jointly. The results include all possible estimates according to their probability of occurrence. In addition, the analysis identifies which parameters are the key influences on results. Risk analysis addresses and in fact, encompasses the approach to sensitivity analysis called for in OMB guidelines.

Modeling Benefits

The model developed to estimate benefits follows directly from the methodology previously discussed. In fact, equating changes in benefits (“utility”) to changes in the quantity and quality of time is convenient because it can draw from extensive literature on the value of time in various activities.

Due largely to data constraints, only use value has been quantified in this analysis. As such, the analysis is conservative – it likely understates the total value of benefits that would be derived by society from the Final Rules. Use value is derived from the anticipated reactions of people with disabilities to changes in access that are tangible and readily quantifiable. User data is generally obtainable through market research and expert opinion. Option and existence values are described instead in qualitative terms.

User benefits are estimated for facility visitors with disabilities who use elements that are affected by the Final Rules.[7]User benefits associated with a direct change in access time are monetized using standard assumptions about the value of time and the type of use. Facility users potentially gain or lose benefits depending on the type of change in access within a facility. Positive and negative benefits are summed for all annual visits to a facility to estimate total net annual benefits. Estimating benefits from changes in access time assumes that all facilities have some level of access.[8]In addition, it is assumed that current users of existing facilities can directly assess the impact of the requirement as a change in access time. Such data consists of minutes saved per use of a facility element.

“Premiums” on the value of time are applied to capture changes in the quality of the user’s experience, and are derived from studies that have documented the increased willingness to pay for improved access and use of transit facilities. For example, economic analysis and market research have shown that people with disabilities would pay a premium to use accessible transit systems if they were made available. In addition, transit riders would also value sitting more than standing without regard to any change in the time it takes to use the service. Data used to assign values to the user experience of changes in access time and use of facilities has been drawn from these sources.

A diagram of the economic model is shown in Figure ES-1. In the base case (e.g. assuming a baseline of the 1991 Standards), the generalized use and access cost is equal to P0. A change in access time at the facility creates P1, the generalized use and access cost of the new or revised standard. This change in generalized use and access cost stimulates additional facility visits, shown by an increase from Q0 to Q1. Total annual user benefits are represented by the shaded area [P0 a b P1.]

Figure ES-1: Economic Framework for Estimating Benefits from Changes in Access Time

Modeling Costs

Cost estimation is performed for a number of cost categories of buildings and requirements. The approach for each can be summarized in a simplified framework. Overall, the incremental cost of compliance for elements includes initial and recurring costs. Initial costs refer to the capital costs incurred for design and construction at the facility to achieve compliance. Recurring costs include operations and maintenance (O&M) and the value of any lost productive space. Lost space occurs when compliance requires additional maneuvering room be set aside in an accessible space. In addition, to maintain compliance with some requirements, facilities will need to incur costs to regularly replace equipment. More stringent requirements involve increased capital costs whereas less stringent requirements offer facilities capital cost savings. Recurring costs follow the same cost structure as capital costs.

The framework for estimating costs is developed for three types of construction (new construction, alterations and barrier removal) and three categories of cost (capital construction costs, O&M and lost productive space). Applied to the types of construction, the framework only differs in parameter values. The cost framework can be simply defined as:

Costijkl = [# of facilitiesij]•[# of elements per facilityik]•[cost per elementjkl]

Where the subscripts are defined as follows:

i denotes the facility;

j denotes the type of construction;

k denotes the requirement; and

l denotes the category of cost.

This framework applies to more and less stringent requirements by altering the sign (positive or negative) on the cost per element, as determined by the type of requirement. All unit costs are incremental to a baseline scenario. The number of elements per facility does not change by type of construction.

Capital Construction Costs

Construction costs per element by type of construction (new construction, alterations and barrier removal) differ on basic levels. Construction costs for new construction and alterations are estimated as the cost differential between complying with the 1991 Standards as compared to the 2010 Standards. This implies that, in most cases, construction costs attributable to new construction or alterations would be subtracted from the costs of both standards, and thus, not be measured. New construction and alterations projects represent planned activities at a site, so the Final Rules represent only a difference in design specifications for projects that were being undertaken anyway. By contrast, compliance with the barrier removal requirement implies that whatever level of access is currently provided at a facility, if barrier removal is required, the full cost of retrofitting is attributable to the Final Rules.

Operations and Maintenance Costs

Incremental costs of compliance are not complete without including incremental annual O&M costs. O&M is commonly expressed as a percentage of the unit costs. Requirements can be grouped by the level of use and/or equipment involved in O&M. These O&M categories include (at an increasing level of cost) standard maintenance, high-use maintenance, extraordinary wear and tear, and equipment maintenance. O&M costs are applied for all types of construction. O&M costs start the year after construction has concluded.

Loss of Productive Space

Some requirements also impact (reduce or increase) the space available for productive uses at a facility. The cost to a facility from lost productive space is included in the analysis because it reflects an annual loss in productivity. This cost is assumed to be larger for barrier removal and alterations than for new construction because existing buildings cannot expand the shell and design options may be limited. Loss of productive space is estimated only for the impact of permanent losses of space that directly affect specific facilities’ revenues. It was assumed that barrier removal will be scheduled and/or managed in such a way as to make any losses due to the temporary unavailability of productive space negligible relative to total impact on revenues.

The cost of lost productive space is the amount of lost space (in terms of square feet) multiplied by the value of building space (per square foot). Data on lost space has been developed by the Department’s architects and independent certified professional cost estimators using standard industry practices. The value of building space has been derived from facility-specific data. Similar to O&M, these costs are applied each year.

Replacement Costs

Some elements added to a building solely to comply with the Final Rules are likely to require replacement during the 40 year period. The cost of replacing the elements adds to the total costs to facilities. For those elements likely to need replacement, the replacement cost is assumed to be equal to the full cost of construction under alterations, except in the case of playgrounds for which unit costs estimates for new construction were used. Only the incremental cost of replacement due to compliance is included.

Results

The primary determination of whether the benefits of the Final Rules exceed costs is the discounted net present value (NPV). A positive net present value increases social resources and is generally preferred. An NPV is computed by summing monetary values of benefits and costs, discounting future benefits and costs using an appropriate discount rate, and subtracting the sum total of discounted costs from the sum total of discounted benefits. All quantified costs and benefits to facilities and the general public are included in this result.

Table ES-1 and Figure ES-2 present total NPV for the primary baseline scenario which assumes that: the safe harbor (SH) is in effect, barrier removal is readily achievable for 50% of elements (RA50), and the 1991 Standards (B1991) serve as the baseline architectural and legal standards. Results for both the 3% and 7% discount rates are shown. Each cost curve is a joint distribution of all uncertainties in the model based on a summation of over 3,000 Monte Carlo simulations.

Under the assumptions used to construct this primary baseline scenario, the results indicate that the Final Rules will have a net positive public benefit – i.e., that benefits will exceed costs. For the uncertainties modeled, the risk analysis indicates zero probability that costs would exceed benefits. The latter is seen from the numbers on the chart representing the 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles of the distribution. The range between the 10th and 90th percentiles represents an 80% confidence interval. This interval can be interpreted as having 80% confidence that the true NPV would be within this range. The most likely NPV is the median (50th) percentile (in the middle of this range).

The 7% discount rate indicates that the 80% confidence interval ranges from $6.2B to $12.7 B, with a median of $9.3B. At 3%, this range ($31.5B to $50.7B) is much wider and slightly more skewed toward positive NPVs. These results indicate a probability of near zero that costs would exceed benefits. Table ES-1 indicates the expected total benefits and costs from users and facilities, respectively.

Table ES-1: Total Net Present Value in Primary Scenario at Expected Value (billions $)

(Under Safe Harbor, 50% Readily Achievable Barrier Removal, 1991 Standards for baseline)

Discount Rate |

Expected NPV | Total Expected PV(Benefits) | Total Expected PV(Costs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3% | $40.4 | $66.2 | $25.8 |

| 7% | $9.3 | $22.0 | $12.8 |

Figure ES-2: Total NPV - Primary Scenario: SH/RA50/B1991; 3% and 7% Discount Rates

The following Figures (ES-3 and 4) show the NPV results for other scenarios.

Figure ES-3 provides an assessment of how NPV changes with different RA assumptions. The chart shows RA at the 0, 50, and 100% levels. The RA scenarios have different costs and benefits, because they apply dissimilar rates of barrier removal as well as different accrual of the benefits associated with them. There are, therefore, two offsetting effects working simultaneously. The first effect pushes costs up as the RA% increases due to a greater number of elements subject to supplemental requirements undergoing barrier removal. The second effect increases the benefits as the RA% increases because the rate of completion of elements related to supplemental requirements is higher, and so are the benefits derived from them. The combination of these effects causes this dissimilar set of curves.

Figure ES-3: NPV Comparison – Alternate Readily Achievable %: SH/ RA0, RA50, RA100/ B1991

Figure ES-4 represents differences in NPV as between the primary baseline and alternate baselines comprised of three IBC editions (IBC 2000, IBC 2003 and IBC 2006), assuming that each of these respective IBC editions apply uniformly to all requirements and facilities. The results indicate that B2000 (IBC 2000) has the highest NPV and B2006 (IBC 2006) has the lowest and B1991 is less than B2003 (IBC 2003). These results are due to changes in the make-up of the set of requirements that are included in each alternative baseline.

Figure ES-4: NPV Comparison – Alternate Baselines: SH/RA100/ B1991, B2000, B2003, B2006

Table ES-2 presents an alternate state- and requirement-specific IBC baseline analysis that shows the estimated impact (in terms of total NPV) of using more refined alternate IBC/ANSI baselines for an illustrative subset of requirements. Since it is not feasible to construct separate IBC baselines for each requirement that precisely track the extent to which the current building or accessibility codes in each respective state or local jurisdiction across the country incorporate IBC or ANSI model code provision which mirror that requirement, a subset of 20 requirements with readily-identifiable IBC/ANSI counterparts was selected for more in-depth study. These requirements were selected for additional research because of their readily identifiable IBC/ANSI counterparts in state or local codes and their predominantly negative net present values. An alternate IBC/ANSI baseline was constructed for each requirement by researching current building and accessibility codes nationwide (i.e., all 50 States, the District of Columbia, and, as applicable, local jurisdictions within States) to identify those jurisdictions that already have adopted its respective IBC/ANSI counterpart(s). Appendix 10 presents a matrix summarizing the results of this research by listing, for each requirement, the State and local jurisdictions that have incorporated equivalent IBC/ANSI model code provisions into their own codes, as well as the types of facilities to which such code provisions apply. Depending on the particular requirement, it is estimated that between 24% and 95% of facilities nationwide are already required to be compliant with a State or local code standard (based on an IBC and/or ANSII provision) that mirrors one of these requirements. Thus, for purposes of these state- and requirement-specific alternate IBC/ANSI baselines, the expected values for NPV were scaled by the appropriate percentages for each requirement.

Table ES-2 shows the results of the alternate state- and requirement specific baselines in terms of total NPV for these requirements. Because these results are based on state- and requirement-specific baselines that reflect the current (rather than estimated or assumed) extent to which equivalent IBC/ANSI model codes have been incorporated into building and accessibility codes nationwide, these results represent the most refined assessment of the NPVs for these requirements that are expected to be realized over the life of these rules. These results assume that, for those State and local jurisdictions which already have incorporated equivalent IBC/ANSI model code provisions into their respective building or accessibility codes, no further action will be necessary with respect to the relevant requirements once the Final Rules become effective. These results also assume that, were the Final Rules not to go into effect, the relevant provisions in these jurisdictions’ building or accessibility codes that mirror one or more of these requirements nonetheless would remain unchanged and enforceable.

Table ES-2: NPV Comparison using Primary (1991 Standards) Baseline and State-by-State Requirement-Specific Alternate IBC/ANSI Baseline

Req. ID |

Requirement | % of Facilities Covered by IBC |

NPV 1991 Baseline (million $) |

NPV IBC/ ANSI Baseline (million $) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Automatic Door Break-Out Openings | 87% | ($8) | ($1) |

| 5 | Door and Gate Surfaces | 53% | ($23) | ($11) |

| 10 | Stairs (Alt/BR) | 95% | ($808) | ($41) |

| 14 | Standby Power for Platform Lifts | 80% | ($8) | ($2) |

| 15 | Power-Operated Doors for Platform Lifts | 51% | ($6) | ($3) |

| 16 | Alterations to Existing Elevators | 70% | ($339) | ($102) |

| 20 | Valet Parking Garages | 52% | $83 | $40 |

| 28 | Water closet clearance in single-user toilet rooms - out swinging door | 49% | ($898) | ($454) |

| 32 | Water closet clearance in single-user toilet rooms - in swinging door | 73% | ($975) | ($266) |

| 35 | Drinking Fountains | 47% | ($66) | ($36) |

| 37 | Side Reach | 72% | ($555) | ($153) |

| 41 | Washing Machines and Clothes Dryers (Scoping) | 31% | ($2) | ($1) |

| 51 | Location of Accessible Route to Stages | 36% | ($152) | ($97) |

| 52 | Wheelchair Space Overlap in Assembly Areas | 86% | ($318) | ($43) |

| 58 | Public TTYS | 31% | ($2) | ($1) |

| 59 | Public Telephone Volume Controls | 31% | ($6) | ($4) |

| 60 | Two-Way Communication Systems at Entrances | 24% | ($9) | ($7) |

| 61 | ATMs and Fare Machines | 31% | ($30) | ($21) |

| 62 | Assistive Listening Systems (technical) | 24% | ($26) | ($20) |

| 68 | Accessible Attorney Areas and Witness Stands | 39% | ($106) | ($64) |

| Sum of Above Requirements | ($4,256) | ($1,288) | ||

The results in Table ES-2 demonstrate that consideration of these state- and requirement-specific alternate IBC/ANSI baselines for this subset of 20 requirements leads to markedly lower incremental costs (and benefits) for these requirements. Based on these alternate IBC/ANSI baselines, the likely net costs for this subset of requirements falls from -$4.3B (1991 Standards baseline) to -$1.3 B (state- and requirement-specific alternate IBC baselines). It is not known, however, what the overall NPV for the final rules would be were state and requirement-specific alternate IBC/ANSI baselines developed and applied for all requirements. Application of such alternate IBC/ANSI baselines might lead to a decrease in monetized benefits for some requirements as compared to the 1991 Standards baseline.

[1] Employees with disabilities are also beneficiaries of requirements that increase access at facilities. However, because limited employment data is available by facility type, most of the assessment of benefits for employees is discussed in the section on unquantified benefits. See Section 6.6.

[2] Initial assumptions concerning the impact of the supplemental requirements on use of recreational facilities by persons with disabilities were that they would permit new independent access where it was currently not possible under the 1991 Standards. Evidence from the expert panel suggested that some people with disabilities may already be using such facilities. Their comments, however, also indicate that the supplemental requirements would generate increased use -- potentially dramatic increases in use -- because of latent demand. These features of demand are captured in the development of the demand curve.

[3] Federal Register, Vol. 69, No. 189: 58768-58786.[4] Federal Register, Vol. 73, No. 117: 34466-34557.

[5] Federal Register, Vol. 73, No. 126: 36964-37055.

[6] New requirements include standards that are not currently being enforced. Among the requirements that are currently being enforced, and therefore do not represent a change and are not included in the assessment, are many of the otherwise “new” requirements applicable to State and local government judicial, detention and correctional facilities.

[7] With respect to elements that are not subject to specific scoping or technical standards in the 1991 Standards, the Department’s current Technical Assistance Manual for Title III provides that “a reasonable number, but at least one” element should be accessible and on an accessible route. Many of the “new” requirements applicable to exercise facilities provide essentially the same thing – that 5% or at least one of each element (exercise machines, lockers, saunas, etc.) be accessible and be on an accessible route. If the “reasonable number but at least one” requirement were to be used, such requirements would not be new, and would in some cases only represent a change for facilities that have more than 20 of a particular element. For purposes of this analysis, however, requirements relating to exercise equipment are modeled as new or “supplemental” requirements.

[8] Such standards include the Uniform Federal Accessibility Standards, the Fair Housing Act, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, and the IBC.

Return to RIA Table of Contents | Next Chapter

March 8, 2011