|

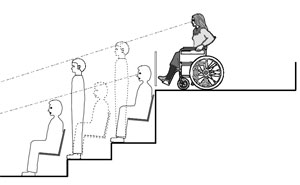

On June 8, 2006, at the court’s request, the Department filed a brief as amicus curiae in a private case pending in federal court in Los Angeles. The central issue in Miller v. The California Speedway Corp. is whether, under section 4.33.3 of the Department’s ADA Standards for Accessible Design, patrons who use wheelchairs must be provided with unobstructed lines of sight over standing spectators in order to see the NASCAR races and other motor sports events held at the racetrack.

In a series of cases in the late 1990s, the Department took the position that section 4.33.3’s “lines of sight comparable” language mandates that public accommodations provide patrons who use wheelchairs with comparable lines of sight over standing spectators at facilities where spectators can be expected to stand during games or events. The Miller case is the first case since that time in which the Department has had an opportunity to reaffirm its position.

|

Figure Showing Comparable Line of Sight for Wheelchair Seating Location

|

The Department has been investigating allegations that PONY Baseball, Inc. (PONY), a youth baseball league in Hilo, Hawaii, has violated the ADA by refusing to allow the father of a player who is deaf to provide sign language interpreting for his son during tournament games. PONY’s rules limit the number of coaches in the game and the league has ruled that the father, who is only providing sign language interpreting, must be included in the total number of coaches for his son’s team.

Settlement negotiations focused initially on a state tournament scheduled to begin June 30, 2006. On June 20, 2006, PONY signed a letter agreement permitting one of the player’s parents to interpret during that tournament. Negotiations are continuing with PONY on remaining settlement terms.

On April 12, 2006, the Department entered into a settlement agreement with the Michigan Department of Human Services (MDHS) resolving two complaints filed by deaf parents who alleged that MDHS had refused to provide them with interpreters when they were interviewed by MDHS case workers during child abuse and neglect investigations involving their children. MDHS agreed to: 1) adopt a new Effective Communication Policy; 2) require case workers to indicate on a revised intake form if a parent has a disability and requires an interpreter for effective communication; 3) issue a public notice regarding Title II’s applicability to MDHS; 4) update its hotline numbers, its website, and other pertinent literature to include a TTY number and the Michigan Relay number; and 5) train its 150 managers and 9,000 employees annually on the ADA and its requirement to provide interpreters when necessary for effective communication.

The Twin Cities Avanti Stores, LLC, of Minneapolis, doing business as Oasis Markets, entered into a settlement agreement with the Department on July 10, 2006, resolving a complaint filed by a local independent living center charging that Oasis Market convenience stores and gas stations were not accessible to people with disabilities, including people who use wheelchairs.

Under the terms of the agreement, barriers in 22 gas station and convenience stores in Minnesota will be removed. Within one year, all parking and external store access remodeling will be completed; within two years all store counters and internal store access remodeling will be completed; and within four years all bathrooms will be remodeled in accordance with the ADA Standards for Accessible Design. In addition, employees of Oasis Markets will be trained to provide refueling assistance to people with disabilities who request such assistance as required by the ADA.

The law office of Cohen and Jaffe, LLC, in New York entered into a settlement agreement with the Department on July 3, 2006, resolving a complaint that the firm had failed to provide a qualified sign language interpreter for a client who is deaf as she prepared for deposition testimony and for other settlement and legal discussions. The firm used the complainant’s mother, who is not a qualified interpreter, to interpret for her daughter, in violation of the requirements of the ADA.

Under the terms of the agreement, the law firm agreed to provide qualified sign language interpreters for clients who are deaf, to post a notice in their offices prominently stating their responsibilities under the ADA, to not pass along the costs of appropriate auxiliary aids and services to clients with disabilities, and to compensate the complainant $7,000.

The owner of the Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) restaurant in Dayton, Tennessee, signed a settlement agreement with the Department on May 11, 2006, resolving a complaint by a woman who is legally blind who alleged that KFC staff had told her repeatedly to leave the premises because she was accompanied by a service animal. KFC agreed to adopt, maintain, and enforce a policy on the treatment of customers using service animals, to provide a copy of the policy to all employees, to provide training on the policy to all current employees, and to incorporate this training into its regular training programs and repeat it for new KFC employees. In addition, KFC posted a sign on its entry door that reads “KFC Always Welcomes Customers with Service Animals” and provided the complainant $5,000 in compensation.

In Newport News, Virginia, the owner of the Historic Hilton Village Parlor Restaurant signed a settlement agreement with the Department on June 1, 2006, resolving a complaint that the restaurant had refused to allow the complainant’s service animal in the restaurant. As part of the agreement, the owner has now posted a sign on the front door of her restaurant welcoming customers with service animals and has agreed to adopt and distribute to all restaurant employees a new policy regarding service animals for customers with disabilities, which is an attachment to the settlement agreement.

The City of Milwaukee, the County of Milwaukee, and a Milwaukee Business Improvement District (BID) entered into a settlement agreement with the Department on July 11, 2006, resolving access concerns at the Milwaukee Riverwalk, a public walkway along the Milwaukee River which was developed by the City of Milwaukee and local property owners, acting through the BID.

Under the agreement, the City, County, and BID have agreed to: 1) construct and install ramps, walkways, or lifts in several locations to ensure that the Riverwalk is readily accessible to and usable by people with mobility disabilities; 2) modify, replace, or install handrails in appropriate locations; 3) modify built up curb ramps by grinding down the surface in two locations; 4) construct an accessible walkway from a parking lot to an existing accessible ramp; and 5) remove existing ramps and install new gangways to floating docks in three locations.

Because a small part of the Riverwalk is located in a different Business Improvement District, the BID for that area has also agreed to install continuous handrails along the sloped walkway to the Riverwalk located in its territory.

The most frequent complaint the Department receives against hospitals under the ADA is the failure to provide appropriate aids and services needed to communicate effectively with people who use sign language as their primary means of communication. The following cases are the Department’s most recent activities to address this problem.

Laurel Regional Hospital in Laurel, Maryland, signed a consent decree on July 14, 2006, with the Department and private plaintiffs resolving a case involving seven people who alleged that the hospital had failed to provide them with appropriate auxiliary aids or services to ensure effective communication with them in the emergency department or during their hospitalizations. This case is different from other hospital cases the Department has participated in previously; in this case, the hospital already had the capability of providing sign language interpreters through a video interpreting service, but when the individuals asked for interpreting services, the hospital either used those services ineffectively or used ineffective or inappropriate alternatives such as paper and pen, lipreading, gesturing, or family members or companions to communicate. The hospital has now installed an enhanced video interpreting system that meets performance standards set forth in the decree.

The South Florida Baptist Hospital in Plant City, Florida, signed an agreement on May 5, 2006, resolving two complaints. One involved a man who alleged that the hospital failed to provide a sign language interpreter prior to his surgery or for post-surgical wound care instructions. The second involved the daughter of the patient who alleged that she was forced into the role of sign language interpreter to facilitate communication between her father and the Hospital’s medical personnel. The hospital has agreed to establish a program to provide appropriate auxiliary aids and services, including sign language interpreters, when needed and to provide visual alarms, captioning and decoders for televisions, and TTYs in patient rooms and all public areas of the hospital.

The McLeod Regional Medical Center in Florence, South Carolina, signed an agreement on July 10, 2006, resolving three complaints against the hospital for failing to secure qualified interpreters when necessary to ensure effective communication with patients who use sign language for communication.

On July 11, 2006, the Department filed a case in federal court in Maryland against Youth Services International (YSI) for failing to provide the auxiliary aids and services needed for effective communication for youth who are deaf or hard of hearing in its facilities. YSI operates juvenile justice facilities and programs in Florida, Georgia, South Dakota, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Iowa, and Minnesota.

The case stems from a complaint from a juvenile who is deaf who alleged that during a 13-month stay at a YSI-operated facility he was permitted only limited access to a sign language interpreter. This lack of access largely prevented him from participating in rehabilitation, counseling, and other social and educational programs offered at the facility. In addition, even when provided an interpreter, he was subjected to segregated housing and limited opportunities for participation in programs. The case has been resolved by a settlement agreement.

In June 2006, the Department delivered $113,250 in checks from a housing developer to 12 present and past residents with disabilities of two apartment complexes in suburbs outside Reno, Nevada, as compensation for the inaccessibility they encountered while living there. The payments, ranging from $2,500 to $23,500, are part of the relief the Department obtained in a design and construction lawsuit under the Fair Housing Act that was resolved by a consent order last year, Silver State Fair Housing Council and United States of America v. ERGS, Inc., et al., (July 12, 2005).

The consent order established a $150,000 settlement fund and provided a six-month period for the Department to locate individuals who were harmed by the inaccessible features at the apartments. After investigating and interviewing potential claimants, the Department submitted its preliminary damages determinations for each individual to the developer, who settled for a lump sum that was then distributed based on the nature, severity, and duration of the harm each individual sustained.

The person who received $23,500 is a man with paraplegia who has lived for three years at one of the complexes. After he requested a ramp at the steps outside his home, the property management firm installed a wooden ramp so steep that it could barely be navigated, for a charge of $300. It also had a one-inch lip at the base and handrails so high they were out of reach. The resident did not ask the management to modify the ramp for fear of being charged again. Last fall, this individual fell out of his wheelchair going down the ramp and injured his right hip.

In addition to the payment of damages to aggrieved persons, the consent order requires accessibility improvements to the apartment units and the complexes’ common areas at an estimated cost of $1.67 million. The agreement also provided $27,500 in damages for the Silver State Fair Housing Council, which initially filed the lawsuit, awarded $250,000 to reimburse its attorney’s fees and litigation expenses, and required the payment of a $30,000 civil penalty.

On June 20, 2006, an Illinois jury ordered the former owner and manager of an apartment building in Marion, Illinois, to pay $15,000 to Deborah Norton Ally, who was told she could not rent an apartment because she used a wheelchair. The jury awarded $5,000 in compensatory damages, $3,000 in punitive damages against the former manager, and $7,000 in punitive damages against the former owner.

In February 2005, the Department filed suit against Zellpac, Inc., and Guy Emery, the former owner and manager, respectively, of the apartment building, alleging they had violated the Fair Housing Act when Emery told Ms. Norton Ally, in the fall of 2001, that he would not rent an available apartment to her because she used a wheelchair. Ms. Norton Ally filed a charge with the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which investigated the charge, found reasonable cause to believe that a discriminatory housing practice had occurred, and referred the matter to the Department of Justice. Zellpac, Inc. is owned by Randy Patchett and Jim Zeller. Zellpac, Inc. subsequently sold the property and Emery no longer works there.

On May 8, 2006, the Department filed a lawsuit against the owners and managers of the Fairway Trails Apartments, in Ypsilanti, Michigan, alleging that the defendants retaliated against a disabled tenant who had requested a reasonable accommodation under the Fair Housing Act. The complaint alleges that the defendants sent the tenant a letter stating that his lease would not be renewed two days after a state court judge ruled in an eviction proceeding that the defendants had to accommodate his disability by allowing him to pay his rent the third week of every month. The tenant received a Social Security Disability check on the third Wednesday of the month. The case was referred to the Justice Department after the Department of Housing and Urban Development received a complaint, conducted an investigation, and issued a charge of discrimination.

On June 30, 2006, the Department filed a federal lawsuit alleging disability discrimination by the County of Sarasota, Florida. The Department’s complaint alleges that the county refused to allow Renaissance Manor, Inc., to operate six homes for individuals with mental illness and a history of substance abuse, although the homes at issue are permitted to operate as a matter of right under the county’s zoning code. The Department contends that the homes, which are intended to provide a supportive environment for residents, are otherwise similar to other houses in the county inhabited by residents sharing living space and common facilities. The complaint also alleges that the county retaliated against Renaissance Manor by refusing to release grant funds it had previously awarded to it.

The suit seeks monetary damages to compensate the victims, civil penalties, and a court order barring future discrimination.

The State of Vermont has reached a settlement agreement with the Department regarding civil rights violations in Vermont State Hospital, a hospital for people with mental health problems, in Waterbury, Vermont. The four year agreement, filed in federal court in Vermont, requires the State to implement reforms to ensure that patients in the facility are adequately protected from harm and provided adequate services including mental health care. The agreement will be supervised by jointly-agreed upon monitors. Under the terms of the agreement, the State will address and correct all of the violations identified by the Department, including the hospital’s failure to protect patients from suicide hazards and undue restraint, failure to provide adequate psychological and psychiatric services, and failure to ensure adequate discharge planning and placement in the most appropriate, integrated setting.

“One of the Attorney General’s stated priorities is protecting the civil rights of all Americans, including these vulnerable institutionalized persons. People with mental health problems in the care of the State are entitled to be safe and provided with adequate treatment,” said Wan J. Kim, Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division.

“The U.S. Attorney’s Office is pleased that the Civil Rights Division and the State of Vermont were able to reach resolution on this important matter,” said Thomas D. Anderson, United States Attorney for the District of Vermont. “We applaud the leadership of Governor James Douglas and his administration in this case, and the State’s prompt implementation of the reforms embodied in the agreement.”

The Civil Rights Division has successfully resolved similar investigations of other psychiatric facilities and has pending investigations concerning psychiatric facilities in Connecticut, Oregon, and the District of Columbia.

The ADA Mediation Program is a Department sponsored initiative intended to resolve ADA complaints in an efficient manner. Mediation cases are initiated upon referral by the Department when both the complainant and the respondent agree to participate. The program utilizes professional mediators who are trained in the legal requirements of the ADA and has proven effective in resolving complaints at less cost and in less time than traditional investigations or litigation. Over 75% of all complaints mediated have been settled successfully.

In this issue, we focus on complaints against restaurants that have been successfully mediated.

In California, a service animal user complained that he was refused service at the same fast-food restaurant on two separate occasions. The restaurant agreed to expand its ADA compliance policy by developing a comprehensive section on serving people who use service animals. It also agreed to provide ongoing training for employees and to have regular visits from unidentified shoppers to verify compliance. The restaurant also agreed to pay the complainant $15,000 in compensation and attorney’s fees. In California, a service animal user complained that he was refused service at the same fast-food restaurant on two separate occasions. The restaurant agreed to expand its ADA compliance policy by developing a comprehensive section on serving people who use service animals. It also agreed to provide ongoing training for employees and to have regular visits from unidentified shoppers to verify compliance. The restaurant also agreed to pay the complainant $15,000 in compensation and attorney’s fees.

A person with a mobility impairment complained that a Pennsylvania pizzeria was inaccessible because of two steps at the entrance. The parties agreed that, because of the location of the steps and city sidewalk, there was not enough room to install a permanent ramp. As an alternative, the restaurant owner obtained a portable ramp, installed a doorbell, and posted a sign instructing customers to ring the bell to alert staff, who would immediately bring the ramp to the entrance. A person with a mobility impairment complained that a Pennsylvania pizzeria was inaccessible because of two steps at the entrance. The parties agreed that, because of the location of the steps and city sidewalk, there was not enough room to install a permanent ramp. As an alternative, the restaurant owner obtained a portable ramp, installed a doorbell, and posted a sign instructing customers to ring the bell to alert staff, who would immediately bring the ramp to the entrance.

In Utah, an individual whose child has a mobility impairment complained that a restaurant did not have an accessible entrance. The parties initially agreed that the restaurant would create a new accessible entrance at the side of the building, but the town refused to issue building permits because it would have encroached on the narrow drive-through service lane. The parties then agreed that the restaurant would obtain a portable ramp, install a doorbell with appropriate signage at the entrance, and train its staff on where the ramp would be stored as well as how to use the ramp. In Utah, an individual whose child has a mobility impairment complained that a restaurant did not have an accessible entrance. The parties initially agreed that the restaurant would create a new accessible entrance at the side of the building, but the town refused to issue building permits because it would have encroached on the narrow drive-through service lane. The parties then agreed that the restaurant would obtain a portable ramp, install a doorbell with appropriate signage at the entrance, and train its staff on where the ramp would be stored as well as how to use the ramp.

A person with a mobility disability complained that a Pennsylvania restaurant did not have an accessible entrance. Because a long ramp was required, the parties agreed to enlist an architect to draw up plans and apply for a zoning variance. The variance was granted, and the compliant ramp was completed. A person with a mobility disability complained that a Pennsylvania restaurant did not have an accessible entrance. Because a long ramp was required, the parties agreed to enlist an architect to draw up plans and apply for a zoning variance. The variance was granted, and the compliant ramp was completed.

In Missouri, a wheelchair user complained that a restaurant’s entrance had a steep, narrow concrete delivery ramp with no directional signage identifying it as the accessible entrance. The restaurant installed a new ramp at its main entrance, restriped the parking lot to provide accessible parking, and installed appropriate signage. In Missouri, a wheelchair user complained that a restaurant’s entrance had a steep, narrow concrete delivery ramp with no directional signage identifying it as the accessible entrance. The restaurant installed a new ramp at its main entrance, restriped the parking lot to provide accessible parking, and installed appropriate signage.

In Tennessee, a disability rights organization complained that one entrance at a fast food restaurant was inaccessible and that the second, an accessible entrance, was locked after dark. The complainants also alleged that there was no signage directing customers with disabilities to the accessible entrance. The restaurant owner agreed to install a ramp and reconstruct the doorway to provide access at the inaccessible entrance and added accessible parking spaces and appropriate signage. In addition to resolving the original complaint, the owner also modified the entrance to the restrooms and installed grab bars to the otherwise accessible toilet stalls, removed barriers to provide an accessible path of travel to the service counter and dining area, added wheelchair accessible tables, and adjusted the height of the pay telephone. In Tennessee, a disability rights organization complained that one entrance at a fast food restaurant was inaccessible and that the second, an accessible entrance, was locked after dark. The complainants also alleged that there was no signage directing customers with disabilities to the accessible entrance. The restaurant owner agreed to install a ramp and reconstruct the doorway to provide access at the inaccessible entrance and added accessible parking spaces and appropriate signage. In addition to resolving the original complaint, the owner also modified the entrance to the restrooms and installed grab bars to the otherwise accessible toilet stalls, removed barriers to provide an accessible path of travel to the service counter and dining area, added wheelchair accessible tables, and adjusted the height of the pay telephone.

In South Carolina, a disability advocacy group complained that a restaurant housed in a historic building was inaccessible. The restaurant renovated both restrooms and installed an accessible ramp so that all sections of the restaurant are now accessible. In South Carolina, a disability advocacy group complained that a restaurant housed in a historic building was inaccessible. The restaurant renovated both restrooms and installed an accessible ramp so that all sections of the restaurant are now accessible.

Relatives of a wheelchair user complained that a North Carolina restaurant lacked accessible restroom facilities. With technical assistance from a local independent living center and the local building inspector, the restaurant constructed a unisex accessible restroom, installed one van-accessible and two standard accessible parking spaces, and created an accessible path of travel from the parking area to the restaurant entrance. Relatives of a wheelchair user complained that a North Carolina restaurant lacked accessible restroom facilities. With technical assistance from a local independent living center and the local building inspector, the restaurant constructed a unisex accessible restroom, installed one van-accessible and two standard accessible parking spaces, and created an accessible path of travel from the parking area to the restaurant entrance.

A person with a heart condition complained that a Rhode Island restaurant’s accessible restroom was not available to people with disabilities because it was routinely occupied by staff using it as a changing room. The restaurant agreed to issue a written policy statement to the staff prohibiting employees from using accessible restrooms as changing rooms except in an emergency. A person with a heart condition complained that a Rhode Island restaurant’s accessible restroom was not available to people with disabilities because it was routinely occupied by staff using it as a changing room. The restaurant agreed to issue a written policy statement to the staff prohibiting employees from using accessible restrooms as changing rooms except in an emergency.

In Wisconsin, a couple complained that they were not allowed to bring food into a restaurant for their young son who has severe food allergies. The owner of the restaurant, who also owns two others, agreed to allow persons to bring outside food into the restaurants if needed due to a disability. The restaurants trained their employees and posted the policy on their websites. In Wisconsin, a couple complained that they were not allowed to bring food into a restaurant for their young son who has severe food allergies. The owner of the restaurant, who also owns two others, agreed to allow persons to bring outside food into the restaurants if needed due to a disability. The restaurants trained their employees and posted the policy on their websites.

In California, persons with mobility impairments complained that a restaurant located on a pier provided only valet parking, and refused to allow individuals to self-park vehicles that have been adapted with hand controls or other modifications. The restaurant informed all valet employees that it would allow customers with disabilities to self-park within the valet parking area if the customer has a modified vehicle or disability that precludes valet staff from driving the vehicle. The restaurant agreed to provide a van-accessible parking space near the restaurant within the valet parking area and an accessible route to the entrance. In California, persons with mobility impairments complained that a restaurant located on a pier provided only valet parking, and refused to allow individuals to self-park vehicles that have been adapted with hand controls or other modifications. The restaurant informed all valet employees that it would allow customers with disabilities to self-park within the valet parking area if the customer has a modified vehicle or disability that precludes valet staff from driving the vehicle. The restaurant agreed to provide a van-accessible parking space near the restaurant within the valet parking area and an accessible route to the entrance.

In Missouri, a wheelchair user complained that a restaurant’s nonsmoking section was inaccessible. Because there was not enough space to install a permanent ramp, the owners agreed to purchase and use a portable ramp. In Missouri, a wheelchair user complained that a restaurant’s nonsmoking section was inaccessible. Because there was not enough space to install a permanent ramp, the owners agreed to purchase and use a portable ramp.

A person with a mobility disability compla

ined that a North Dakota restaurant did not provide accessible seating in the nonsmoking location. The

restaurant agreed to create an accessible nonsmoking area, implement a reservat

ion system for accessible tables, and provide staff training on the ADA.

In California, a couple with mobility impairments complained that a nation al chain restaurant refused their request to sit in cha irs at the end of a booth, because their disabilities made it difficult to ente r and exit booth seating. They also complained that the manager was rude to them. The restaurant agreed to add accessible, free-standing tables and chairs in addition to booth seating and disciplined the m anager involved in the incident. The restaurant also wrote a letter of apology to the couple, offered them a complimentary meal whe n the new seating had been installed, and paid them $400. In California, a couple with mobility impairments complained that a nation al chain restaurant refused their request to sit in cha irs at the end of a booth, because their disabilities made it difficult to ente r and exit booth seating. They also complained that the manager was rude to them. The restaurant agreed to add accessible, free-standing tables and chairs in addition to booth seating and disciplined the m anager involved in the incident. The restaurant also wrote a letter of apology to the couple, offered them a complimentary meal whe n the new seating had been installed, and paid them $400.

A wheelchair user complained that a New Mexico restaurant’s restrooms were inaccessible. The owner of the restaurant modified the restrooms, including reconfiguring toilet stall partitions to allow clear space for out-swinging stall doors, repositioning fixtures to provide clear floor space, repositioning dispensers to comply with reach range requirements, insulating exposed lavatory pipes, and installing accessible door hardware on toilet stall doors. The restaurant owner also installed two freestanding tables to accommodate wheelchair users in both the smoking and non-smoking sections of the restaurant. A wheelchair user complained that a New Mexico restaurant’s restrooms were inaccessible. The owner of the restaurant modified the restrooms, including reconfiguring toilet stall partitions to allow clear space for out-swinging stall doors, repositioning fixtures to provide clear floor space, repositioning dispensers to comply with reach range requirements, insulating exposed lavatory pipes, and installing accessible door hardware on toilet stall doors. The restaurant owner also installed two freestanding tables to accommodate wheelchair users in both the smoking and non-smoking sections of the restaurant.

On May 22 and the 23, Division staff answered questions and disseminated ADA information to an estimated 700 attendees at the 2006 Annual Conference on Independent Living, sponsored by the National Council on Independent Living at the Grand Hyatt Hotel in Washington, DC. On May 22 and the 23, Division staff answered questions and disseminated ADA information to an estimated 700 attendees at the 2006 Annual Conference on Independent Living, sponsored by the National Council on Independent Living at the Grand Hyatt Hotel in Washington, DC.

From May 21-25, Division staff participated in the American Jail Association Conference in Salt Lake City, Utah.

On June 1, Division staff participated in a panel discussion entitled “ADA: Accomplishments & Challenges” at Loyola College Columbia Campus in Maryland. This one-day event was sponsored by the National Capital Area Disability Support Services Coalition (NCADSSC) for support service and educational professionals. On June 1, Division staff participated in a panel discussion entitled “ADA: Accomplishments & Challenges” at Loyola College Columbia Campus in Maryland. This one-day event was sponsored by the National Capital Area Disability Support Services Coalition (NCADSSC) for support service and educational professionals.

On June 8-10, Division staff gave several presentations at the 2006 Disability Access Conference sponsored by the Disability and Communication Access Board and the Pacific ADA & IT Center at the Hawaii Convention Center in Honolulu, Hawaii. The seminars and panel discussions addressed various facets of Titles II and III of the ADA. The conference was attended by approximately 2000 government officials, employers, design pro-fessionals, disability service agencies, and advocates. In addition, staff answered questions and disseminated ADA information at a “Tools for Life” Expo highlighting assistive technology and services for people with disabilities that was held in conjunction with the conference. On June 8-10, Division staff gave several presentations at the 2006 Disability Access Conference sponsored by the Disability and Communication Access Board and the Pacific ADA & IT Center at the Hawaii Convention Center in Honolulu, Hawaii. The seminars and panel discussions addressed various facets of Titles II and III of the ADA. The conference was attended by approximately 2000 government officials, employers, design pro-fessionals, disability service agencies, and advocates. In addition, staff answered questions and disseminated ADA information at a “Tools for Life” Expo highlighting assistive technology and services for people with disabilities that was held in conjunction with the conference.

On June 22, Division staff gave a presentation at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s annual Technical Assistance Program for Small Business Conference in Lincolnshire, Illinois. The presentation addressed reasonable acco-mmodation requirements under the ADA. The audience consisted of employers and small business owners. On June 22, Division staff gave a presentation at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s annual Technical Assistance Program for Small Business Conference in Lincolnshire, Illinois. The presentation addressed reasonable acco-mmodation requirements under the ADA. The audience consisted of employers and small business owners.

On June 26, Division staff joined representatives from the Department of Labor and the EEOC for a panel discussion at the annual conference of the Society for Human Resource Management in Washington, DC. The ADA and its relevance to employers was discussed. On June 26, Division staff joined representatives from the Department of Labor and the EEOC for a panel discussion at the annual conference of the Society for Human Resource Management in Washington, DC. The ADA and its relevance to employers was discussed.

On June 28 through 30, Division staff represented the Department at an invitation-only working Conference on Emergency Management and Individuals with Disabilities and the Elderly in Washington, sponsored by the Departments of Health and Human Services and Homeland Security. The conference addressed three phases of emergency management – planning, response, and recovery. In the morning invitees heard from experts on the topics of the day and in the afternoons there were separate working sessions for State delegations and for the Interagency Coordinating Council on Emergency Preparedness for Individuals with Disabilities (established by Presidential Executive Order) with national organizations. Staff gave two presentations at the conference: one addressed the disability-related findings and recommendations in the Nationwide Plan Review Report (NPR Report) of States’ and local governments’ emergency operations planning and described the process leading to those findings; the second presentation addressed accessibility concerns relating to post-disaster reconstruction. Attendees include Federal representatives; individuals designated by Governors from offices related to Aging, Health, Homeland Security, Emergency Management, and Special Needs Populations; and, from each State, an individual representing the disability perspective. On June 28 through 30, Division staff represented the Department at an invitation-only working Conference on Emergency Management and Individuals with Disabilities and the Elderly in Washington, sponsored by the Departments of Health and Human Services and Homeland Security. The conference addressed three phases of emergency management – planning, response, and recovery. In the morning invitees heard from experts on the topics of the day and in the afternoons there were separate working sessions for State delegations and for the Interagency Coordinating Council on Emergency Preparedness for Individuals with Disabilities (established by Presidential Executive Order) with national organizations. Staff gave two presentations at the conference: one addressed the disability-related findings and recommendations in the Nationwide Plan Review Report (NPR Report) of States’ and local governments’ emergency operations planning and described the process leading to those findings; the second presentation addressed accessibility concerns relating to post-disaster reconstruction. Attendees include Federal representatives; individuals designated by Governors from offices related to Aging, Health, Homeland Security, Emergency Management, and Special Needs Populations; and, from each State, an individual representing the disability perspective.

On July 7, Division staff made two presentations at the Virginia ADA Coalition’s annual conference, attended by approximately 100 ADA Coordinators and individuals with disabilities, in Charlottesville, Virginia. One presentation addressed how to file complaints and how the Department processes and investigates complaints. The second provided an overview of Project Civic Access and described the issues typically encountered. On July 7, Division staff made two presentations at the Virginia ADA Coalition’s annual conference, attended by approximately 100 ADA Coordinators and individuals with disabilities, in Charlottesville, Virginia. One presentation addressed how to file complaints and how the Department processes and investigates complaints. The second provided an overview of Project Civic Access and described the issues typically encountered.

From July 8-11, Division staff answered questions and disseminated ADA information to an estimated 20,000 attendees at the 2006 National Council of LaRaza (NCLR) Annual Conference and Latino Expo USA, held at the Los Angeles Convention Center in Los Angeles, California. From July 8-11, Division staff answered questions and disseminated ADA information to an estimated 20,000 attendees at the 2006 National Council of LaRaza (NCLR) Annual Conference and Latino Expo USA, held at the Los Angeles Convention Center in Los Angeles, California.

On July 13, Division staff participated in two panel discussions at the National Association for Court Management Conference in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. Panelists discussed the provisions of the ADA and the Architectural Barriers Act as they apply to the nation’s courts and addressed common access issues and solutions to them. On July 13, Division staff participated in two panel discussions at the National Association for Court Management Conference in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. Panelists discussed the provisions of the ADA and the Architectural Barriers Act as they apply to the nation’s courts and addressed common access issues and solutions to them.

On July 14, Division staff gave a presentation on the ADA to the program directors of Serve DC, the DC Commission for National and Community Service. On July 14, Division staff gave a presentation on the ADA to the program directors of Serve DC, the DC Commission for National and Community Service.

From July 15-18, Division staff, participated in the 2006 NAACP 97th Annual Convention and 37th Commerce & Industry Show at the Washington Convention Center in Washington, DC. Staff answered questions and disseminated ADA information to an estimated 16,000 attendees. From July 15-18, Division staff, participated in the 2006 NAACP 97th Annual Convention and 37th Commerce & Industry Show at the Washington Convention Center in Washington, DC. Staff answered questions and disseminated ADA information to an estimated 16,000 attendees.

During the week of July 18-22, Division staff participated in two sessions at the annual conference of the Association for Higher Education and Disability (AHEAD) in San Diego, California. Staff chaired a panel entitled “It’s Not Your Parents’ Cam-pus: Accessible Housing, Transportation, Health Care, Emergency Preparedness,” with participation from repre-sentatives of the Department of Education and During the week of July 18-22, Division staff participated in two sessions at the annual conference of the Association for Higher Education and Disability (AHEAD) in San Diego, California. Staff chaired a panel entitled “It’s Not Your Parents’ Cam-pus: Accessible Housing, Transportation, Health Care, Emergency Preparedness,” with participation from repre-sentatives of the Department of Education and

Ohio State University, and participated in a pre-conference institute providing an overview of disability issues in higher education. Ohio State University, and participated in a pre-conference institute providing an overview of disability issues in higher education.

On July 18, Division staff participated in a teleconference sponsored by the Great Lakes ADA & IT Center in Chicago, Illinois. Staff provided an update on the Department’s ADA activities, followed by an question and answer session. On July 18, Division staff participated in a teleconference sponsored by the Great Lakes ADA & IT Center in Chicago, Illinois. Staff provided an update on the Department’s ADA activities, followed by an question and answer session.

On August 4 and 5, Division staff participated on a legal panel and made a presentation on historic buildings at the Kennedy Center’s Leadership Exchange in Arts and Disability (LEAD) conference in Washington, DC. On August 4 and 5, Division staff participated on a legal panel and made a presentation on historic buildings at the Kennedy Center’s Leadership Exchange in Arts and Disability (LEAD) conference in Washington, DC.

October 09, 2008

|