Faces of the ADA

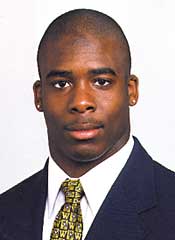

Toure Butler

Michael Hunsinger, Toure's attorney -- "Toure is a great young man who just needed a fair chance to prove himself in school... the ADA gave him that chance"

ABC Sports’ "Player of the Game" in the University of Washington’s 1998 victory over Brigham Young University almost didn’t get the chance to play football. In fact, Toure Butler almost didn’t get the chance to attend classes.

Ever since he was a child, Toure had difficulty understanding material he read, no matter how many times he read it, and struggled through school. But one of his six older brothers took him under his wing, and somehow Toure got by. Eventually, the school district tested him and realized he had a learning disability that affects his ability to process information he reads. Like most people who have dyslexia or other learning disabilities, Toure could understand the information if presented in different formats or in non-traditional ways. For example, in addition to reading a book for class, students with learning disabilities might also watch a play about the book or listen to it on tape.

Once his disability was identified, Toure’s school placed him in college preparatory classes taught in ways that allowed him to learn. With hard work and the right classes, Toure graduated from Cascade High School in Everett, Washington. Based on his grades and test scores, he was accepted by the University of Washington and offered a full athletic scholarship."I wasn't looking at it as just coming to college to get to the pros," Toure told the Seattle Times. "I look at it to further my education. That's the most important part. You aren't always going to have football. I wanted to come to college to get an education. Football is second."

Toure arrived on the Seattle campus in August 1996 and reported for football practice. But after moving into the dorms and practicing for two weeks, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) told him he could no longer play for the Huskies. The University had no option - it had to remove him from the football team and pull his scholarship. For Toure, the loss of the scholarship meant the end of his dream of attending college. Because of his family's financial situation, he could not afford to pay the tuition to the University of Washington. Even the local community college was not a possibility.

The NCAA determined that Toure did not meet its academic eligibility requirements. Because of the volume of requests for eligibility, some students playing summer and fall sports did not receive notification of their eligibility status until after the start of school. The NCAA requires that any freshman participating in college sports must have an acceptable standardized test score, a satisfactory grade point average in high school, and a certain number of "core courses" in English, math and science. Toure had the necessary test scores and grade point average, but the NCAA would not accept Toure’s core courses because they were taught in non-traditional ways. Toure was one of hundreds of students with learning disabilities whose lives were being turned upside down by NCAA’s eligibility rulings.Toure filed an ADA lawsuit, arguing that NCAA’s refusal to recognize courses modified to accommodate students with learning disabilities violated the law. The Department intervened and a federal judge granted Toure an injunction that allowed him to remain at the University of Washington. Eventually, the Department and the NCAA entered into an agreement monitored by the Federal Court in which the NCAA agreed to change its policies and procedures for determining eligibility. Among other things, the NCAA agreed to more closely analyze courses specifically designed for students with learning disabilities and to certify them as "core courses" if they provide students with the same skills and knowledge as those offered to other college-bound students.

Now in his fourth year of college, Toure is well on his way to graduating with a degree in sociology. When the ADA gave him a chance to prove himself in the classroom, Toure passed with flying colors.

July 21, 2000